Severe PARDS in an Infant with a Rare FARSA Mutation Treated with Bronchoscopic Segmental Insufflation and Surfactant Therapy

Abstract

Introduction: Pediatric Acute Respiratory Distress Syndrome (PARDS) is a life-threatening condition characterized by severe hypoxemic respiratory failure and lung inflammation. The pathophysiology involves surfactant inactivation and deficiency, leading to decreased lung compliance. Traditional endotracheal surfactant administration often yields inconsistent results due to inhomogeneous distribution. This case report evaluates the efficacy of bronchoscopic segmental insufflation and surfactant therapy in a patient with severe PARDS and a rare genetic mutation.

Methods: A 4-month-old female infant with severe PARDS (oxygen saturation index (OSI): 25), growth failure, and chronic diarrhea was admitted. Due to refractory hypoxemia despite optimized ventilation (FiO2: 100%, PIP: 35 cmH2O, SIMV ventilation mode), a bronchoscopic intervention was performed. The procedure involved the removal of mucopurulent secretions and the administration of a total surfactant dose of 200 mg/kg (poractant alfa). The surfactant was delivered to each lobe separately using a "wedge" position, followed by pressure-controlled insufflation (30 cmH2O for 30 seconds per segment, consisting of one initial insufflation, followed by surfactant instillation and two additional insufflation cycles) to optimize distribution.

Results: Marked clinical improvement was observed following the bronchoscopic intervention: PIP decreased from 35 to 21 cmH2O, and OSI improved from 25 to 8. Oxygen saturation rose from 88% to 95% despite lower ventilator settings. A second identical procedure was performed two weeks later due to persistent mucus plugging and the patient was successfully extubated three days thereafter. Whole Exome Sequencing (WES) ultimately identified a homozygous c.883C>T mutation in the FARSA gene, confirming a diagnosis of Rajab interstitial lung disease.

Conclusion: Bronchoscopic segmental insufflation combined with surfactant instillation may be considered as a potential adjunctive strategy in selected cases of severe PARDS refractory to conventional management. This technique allows targeted delivery to affected lung regions, facilitates airway secretion clearance, and provides additional diagnostic utility through bronchoalveolar lavage.

Introduction

Pediatric Acute Respiratory Distress Syndrome (PARDS) is a life-threatening, heterogeneous condition characterized by widespread lung inflammation, alveolar edema, and severe hypoxemic respiratory failure (1, 2). Mortality rates remain high, particularly in severe cases, making clinical management critically important (3). The pathophysiology of PARDS is fundamentally driven by a reduction in surfactant synthesis due to type II cell damage, plasma protein leakage, and surfactant inactivation triggered by inflammatory mediators. The "vicious cycle" of surfactant catabolism and inflammation leads to a significant loss of lung compliance and the disruption of alveolar-capillary barrier function. While the primary management strategy for PARDS remains protective ventilation, surfactant therapy may be considered a potential adjunctive option in selected cases of severe disease refractory to conventional management (4,5). However, studies utilizing traditional endotracheal instillation have often failed to show consistent mortality benefits, primarily because surfactant tends to remain in the proximal airways and fails to distribute homogeneously to the damaged alveoli, while also being susceptible to mechanical removal of the protective airway surfactant coating (6).

Recently, the technique of bronchoscopic segmental insufflation combined with surfactant instillation initially developed for persistent atelectasis has emerged as a promising alternative for delivering surfactant directly to target lobes and optimizing alveolar recruitment (7, 8). In this case report, we present the clinical success of bronchoscopic segmental insufflation and surfactant instillation in a patient with severe PARDS who remained unresponsive to conventional treatments.

Case Description

A 4-month-old female infant was admitted to the intensive care unit with severe respiratory failure and clinical PARDS, necessitating the initiation of invasive mechanical ventilation. Her medical history revealed a term birth (37 weeks, 2800 g) via normal spontaneous vaginal delivery with no history of neonatal hospitalization. At 2.5 months of age, she had been hospitalized for two weeks due to SARS-CoV-2 pneumonia and chronic diarrhea. One month following her discharge, she was readmitted to the intensive care unit after developing cyanosis, respiratory distress during feeding, and a worsening general condition. Clinical findings upon admission included growth failure, chronic diarrhea, hypotonia, and a chronic cough. It was noted that during previous emergency department visits for cough and cyanosis following the neonatal period, her oxygen saturation levels were consistently low, ranging between 85% and 90%.

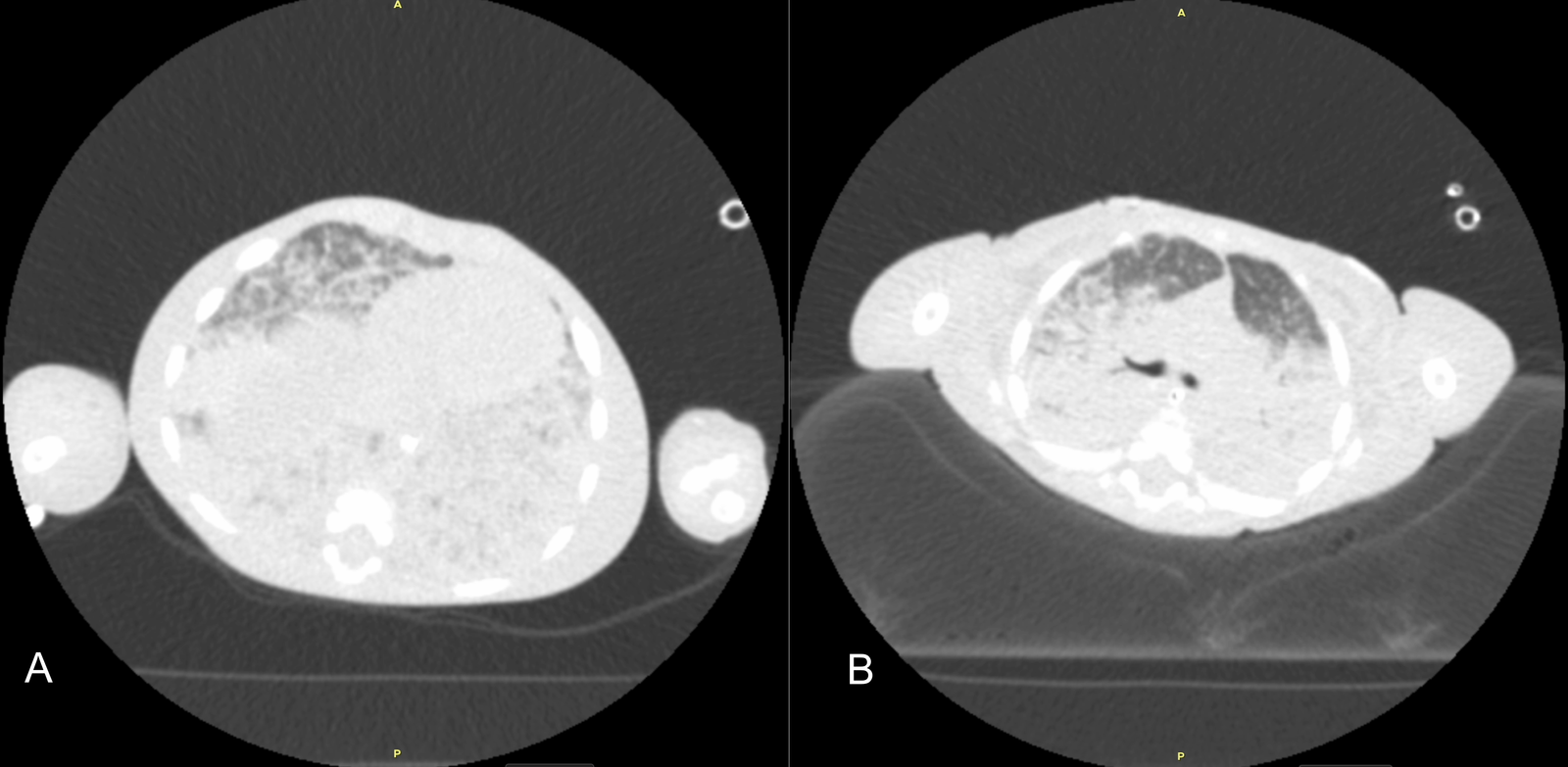

Initial diagnostic workups for immunodeficiency and metabolic diseases were normal; however, a sweat test could not be performed due to the patient's poor general condition and malnutrition. Echocardiography showed no cardiac disease, and abdominal ultrasound was normal. Due to parental consanguinity and a history of a sibling death at 9 months with similar clinical symptoms, a congenital genetic disease with associated interstitial lung disease (ILD) was primarily suspected. Consequently, clinical genetics was consulted, and Whole Exome Sequencing (WES) analysis was initiated. The severity of hypoxemia was assessed using the Oxygen Saturation Index (OSI) and the patient was diagnosed with PARDS based on acute hypoxemia, an OSI of 25, and chest X-ray findings showing new-onset bilateral diffuse alveolar infiltration and pulmonary parenchymal edema (1,2) (Figure 1). Initial axial chest computed tomography was performed at ICU admission, demonstrating diffuse bilateral ground-glass opacities and consolidations (Figure 2A, 2B). Thoracic ultrasound identified bilateral pleural effusions (7 mm on the right and 10 mm on the left). Due to elevated acute phase reactants (WBC: 57 x 109/L, CRP: 33 mg/L), antibiotic therapy was initiated with Vancomycin and Meropenem, alongside appropriate symptomatic PARDS management.

During follow-up, the patient's condition remained critical, with persistent oxygenation failure despite optimized ventilation support. Her ventilator requirements did not decrease, maintaining a PIP of 35 cmH₂O, PEEP of 9 cmH₂O, and FiO₂ of 100% under SIMV ventilation mode, resulting in an oxygen saturation of only 88%. No additional alveolar recruitment maneuvers beyond standard ventilatory optimization were performed prior to bronchoscopy. Due to the refractory nature of her condition, the pediatric pulmonology department decided to perform a bronchoscopic intervention with surfactant instillation and lung insufflation. Additionally, as initial blood and endotracheal aspirate cultures were negative, bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL) sampling was planned during the procedure to further investigate the etiology.

Procedure

Flexible bronchoscopy (Olympus 3.1 mm LF-DP) was performed under general anesthesia using midazolam and propofol through an endotracheal tube (ETT) with an internal diameter of 4.0 mm. Initially, the airways were evaluated for any abnormalities; the airway anatomy was found to be normal. However, profuse yellow-green mucopurulent secretions were observed in all lung segments starting from the carina level, with dense mucus plugging resulting in easy compressibility of the segmental bronchial orifices in the right lower lobe.

Bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL) samples were collected and sent for microbiological and cytological analysis. The total surfactant dose was calculated as 200 mg/kg of poractant alfa (Curosurf), consistent with the standard endotracheal dosage. A dose of 100 mg/kg was administered to the left lung, divided equally as 50 mg/kg to the left upper lobe and 50 mg/kg to the left lower lobe. A dose of 100 mg/kg was administered to the right lung, divided equally among the three lobes. To perform lung insufflation, 2 L/min of oxygen was connected to the bronchoscopy suction port, with airway pressures of 30 cmH2O applied for 30 seconds. This insufflation protocol consisted of one initial insufflation followed by surfactant instillation and two additional insufflation cycles (7).

Airway pressures were continuously monitored via the ventilator during insufflation. The bronchoscope was placed in a "wedge" position in each lung lobe for the instillation of the calculated surfactant dose, followed by a 30-second pause while the scope was slightly withdrawn. In each lobe receiving surfactant, this three-cycle insufflation protocol was applied separately to all segments to optimize surfactant distribution. Following the procedure, the patient was transferred back to the intensive care unit and was placed in a prone position thirty minutes after the procedure to further facilitate surfactant distribution.

Outcome

Following the bronchoscopic intervention, a marked improvement in ventilator parameters and oxygenation was observed; pre-procedural settings were PIP 35 cmH2O and PEEP 9 cmH₂O with an OSI of 25, improving to PIP 21 cmH2O, PEEP 6 cmH₂O, and an OSI of 8 upon completion of the intervention. Despite the high pressure requirements prior to the procedure, the patient's oxygen saturation rose from 88% to 95% with lower ventilator settings, indicating a marked improvement in oxygenation. Following the identification of Pseudomonas aeruginosa in the BAL culture, Vancomycin was discontinued on the 7th day, and the antibiotic regimen was revised to meropenem and amikacin. Although an extubation attempt was made 72 hours post-procedure, the patient could not tolerate it.

Simultaneous echocardiography revealed new-onset dilation of the left heart chambers; consequently, furosemide and milrinone infusions were administered for three days, along with an albumin infusion to treat hypoalbuminemia. Despite observing clinical and radiological improvements, the patient remained unable to be extubated, leading to a repeat of the bronchoscopic procedure using the same technique two weeks later. This second bronchoscopy revealed a significant reduction in mucopurulent secretions, with mucus plugs persisting only in the segments of the right lower lobe.

A second weight-adjusted dose of surfactant was administered lobarly following the same protocol, and no desaturation occurred during the procedure. Both procedures were well tolerated, and no procedure-related complications were observed during or after the interventions. The patient was successfully extubated three days after the second surfactant application (Figure 3). Following extubation, the patient remained clinically stable, showed significant radiological improvement, and was subsequently transferred to the ward. Subsequent Whole Exome Sequencing (WES) analysis identified a homozygous c.883C>T mutation in the FARSA gene. It was concluded that the patient's respiratory symptoms were secondary to interstitial lung disease (Rajab interstitial lung disease) associated with this specific homozygous mutation.

Discussion

Surfactant dysfunction in children with Pediatric Acute Respiratory Distress Syndrome (PARDS) is characterized by both qualitative and quantitative impairments that directly impact lung dynamics (4,5,6). Exogenous surfactant works by reducing surface tension at the air-liquid interface of the alveoli, which increases lung compliance and functional residual capacity while simultaneously decreasing alveolar edema (3,4). A primary reason why surfactant therapy is not routinely recommended in the literature is the challenge of achieving homogeneous delivery to damaged lung regions in severe PARDS cases (9). In our case, the use of flexible bronchoscopy for segmental surfactant instillation combined with pressure-controlled insufflation provided critical advantages in overcoming these barriers (6). Direct administration to each lobe and segment using the bronchoscopic wedge technique minimized the loss of the protective airway surfactant coating and prevented gravity-dependent heterogeneous distribution (6). The insufflation cycles of 30 cmH2O for 30 seconds applied during the procedure were instrumental in overcoming critical opening pressures, thereby optimizing the peripheral spread and absorption of the surfactant (7). Furthermore, the aspiration of dense mucopurulent secretions during the procedure provided immediate mechanical relief and enabled the identification of specific pathogens, such as Pseudomonas aeruginosa, through bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL) analysis. In our patient, the intervention was temporally associated with a substantial reduction in ventilator pressure requirements (approximately 50%), with sustained improvement during follow-up (10). In accordance with literature suggesting potential benefits of repeated surfactant dosing over single-dose applications, the second intervention in our patient was followed by successful extubation (11).

The patient's systemic findings, history of a sibling death, and parental consanguinity raised suspicion of an underlying rare congenital genetic disease, leading to WES analysis (12,13). The identified homozygous FARSA mutation explains the clinical presentation, which included early-onset interstitial lung disease, growth failure, hypotonia, and feeding difficulties (14,15). The FARSA homozygous mutation is a hereditary condition associated with Rajab interstitial lung disease and multisystem involvement, including potential brain calcifications (13–16). Identifying this underlying etiological factor has allowed for close clinical monitoring of future systemic involvements and the implementation of early therapeutic strategies. The identification of the biallelic FARSA variant provides a plausible pathophysiological framework linking the underlying Rajab interstitial lung disease (ILD) to impaired surfactant homeostasis. FARSA encodes the alpha subunit of cytoplasmic phenylalanyl-tRNA synthetase (FARS1), a heterotetrameric enzyme essential for protein translation and cellular proteostasis (12). Type II alveolar epithelial cells, which function as specialized "protein factories" for the continuous synthesis and secretion of surfactant proteins (SP-A, B, C, and D), are particularly vulnerable to disturbances in this translation machinery (14). We hypothesize that FARSA-related cellular stress stemming from impaired aminoacylation and endoplasmic reticulum (ER) stress may reduce the capacity of Type II cells to maintain a functional surfactant pool, thereby predisposing the lung to a baseline state of surfactant deficiency (12–16). In this context, the superimposed inflammatory injury of severe PARDS may have acted as a "second hit," whereby inflammatory mediators and increased alveolar–capillary permeability further exacerbated surfactant dysfunction through secondary inactivation. This combined mechanism offers a plausible rationale for targeted exogenous surfactant delivery via bronchoscopic segmental insufflation, potentially compensating for the underlying production defect and contributing to clinical stabilization. While causality cannot be definitively inferred from a single case, this proposed link highlights the potential relevance of individualized therapeutic strategies in genetic surfactant-related lung diseases.

Our study has several limitations. As a single-case report without a control group, our findings are inherently limited in their generalizability. During the first bronchoscopic procedure, the clearance of widespread mucus plugs may have independently played a significant role in the rapid improvement of the patient's oxygenation, making it difficult to distinguish the contribution of surfactant therapy from mechanical airway clearance. Several concurrent interventions, including prone positioning shortly after the procedure, subsequent antimicrobial adjustment, and cardiovascular optimization, may also have influenced the observed clinical course. However, the achievement of similar clinical success during the second procedure, despite a significantly lower mucus burden and followed by successful extubation, supports a potential independent therapeutic contribution of the surfactant and segmental insufflation combination.

The reported outcomes primarily reflect short-term physiological improvement, and long-term respiratory outcomes could not be assessed. Additionally, this technique requires advanced bronchoscopic expertise and close integration between pediatric intensive care and pulmonology teams, which may limit its widespread applicability. Nevertheless, the fact that both PARDS and the underlying interstitial lung disease (ILD) associated with the FARSA mutation are characterized by surfactant deficiency and dysfunction provides a pathophysiological rationale for this therapeutic approach.

Conclusion

In the management of severe Pediatric Acute Respiratory Distress Syndrome (PARDS), bronchoscopic segmental insufflation combined with surfactant instillation may represent a promising adjunctive approach in selected cases refractory to conventional ventilator strategies. Beyond enabling targeted surfactant delivery, the technique also offers additional benefits through airway secretion clearance and diagnostic evaluation via bronchoalveolar lavage. In carefully selected patients, the use of this technique may be associated with improvements in oxygenation and progression toward ventilator weaning. However, larger prospective studies are required to better define the safety, efficacy, and definitive role of this modified approach in the management of severe PARDS.

Ethical Statement

Written informed consent for the procedure was obtained from the patient's parents. Ethics committee approval was not required in accordance with institutional policies.

Conflict of interest

The authors have no conflict of interest to disclose.

Data availability statement

Data sharing is not applicable to this article as no datasets were generated or analyzed during the current study.

Author contributions

All authors contributed to the study's concept and design and participated in the clinical management of the patient. Özge Meral was the lead author of the case report and prepared the initial draft of the manuscript. Aylin Erkul, İkbal Türker and Hamza Polat, who were involved in the patient's management, critically reviewed the manuscript and made significant revisions. All authors have read and approved the final version of the manuscript for publication.

References

1. Pediatric Acute Lung Injury Consensus Conference Group. Pediatric acute respiratory distress syndrome: consensus recommendations from the Pediatric Acute Lung Injury Consensus Conference. Pediatr Crit Care Med. 2015;16(5):428–439. doi: 10.1097/PCC.0000000000000350

2. Miller AG, Curley MAQ, Destrampe C, Flori H, Khemani R, Thomas NJ, et al. A master protocol template for pediatric ARDS studies. Respir Care. 2024;69(10):1284–1293. doi: 10.4187/respcare.11839

3. Rodríguez-Moya VS, Gallo-Borrero CM, Santos-Areas D, Prince-Martínez IA, Díaz-Casañas E, López-Herce Cid J. Exogenous surfactant and alveolar recruitment in the treatment of acute respiratory distress syndrome. Clin Respir J. 2016;11(6):1032–1039. doi: 10.1111/crj.12462

4. Lewis JF, Veldhuizen R. The role of exogenous surfactant in the treatment of acute lung injury. Annu Rev Physiol. 2003;65:613–642. doi: 10.1146/annurev.physiol.65.092101.142434

5. Emeriaud G, López-Fernández YM, Iyer NP, Bembea MM, Agulnik A, Barbaro RP, et al. Executive summary of the second international guidelines for the diagnosis and management of pediatric acute respiratory distress syndrome (PALICC-2). Pediatr Crit Care Med. 2023;24(2):143–168. doi: 10.1097/PCC.0000000000003147

6. De Luca D, Cogo P, Kneyber MC, Biban P, Semple MG, Perez-Gil J, et al. Surfactant therapies for pediatric and neonatal ARDS: ESPNIC expert consensus opinion for future research steps. Crit Care. 2021;25:75. doi: 10.1186/s13054-021-03489-6

7. Šapina M, Olujic B, Nađ T, Vinkovic H, Dupan ZK, Bartulovic I, et al. Bronchoscopic treatment of pediatric atelectasis: a modified segmental insufflation–surfactant instillation technique. Pediatr Pulmonol. 2024;59(3):625–631. doi: 10.1002/ppul.26792

8. Stafler P, Zeitlin Y, Dotan M, Shostak E. Bronchoscopic lung insufflation and surfactant instillation for post-cardiac surgery atelectasis in a neonate. Pediatr Interv Pulmonol. 2025;2(1):15–17.

9. Puntorieri V, Qua Hiansen J, McCaig LA, Yao LJ, Veldhuizen RAW, Lewis JF. The effects of exogenous surfactant administration on ventilation-induced inflammation. BMC Pulm Med. 2013;13:55. doi: 10.1186/1471-2466-13-67

10. Schousboe P, Uslu B, Schousboe A, Nebrich L, Wiese L, Verder H, et al. Lung surfactant deficiency in severe respiratory failure: a potential biomarker for clinical assessment. Diagnostics. 2025;15:847. doi: 10.3390/diagnostics15070847

11. Cai J, Su Z, Zhou Y, Shi Z, Xu Z, Liu J, et al. Beneficial effect of exogenous surfactant in infants suffering acute respiratory distress syndrome after cardiac surgery. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. 2011;40(3):557–562. doi: 10.1016/j.ejcts.2011.01.008

12. Guo R, Chen Y, Hu X, Qi Z, Guo J, Li Y et al. Phenylalanyl-tRNA synthetase deficiency caused by biallelic variants in the FARSA gene and literature review. BMC Med Genomics. 2023;16:155. doi: 10.1186/s12920-023-01662-0

13. Kim SY, Ko S, Kang H, Kim MJ, Moon J, Lim BC, et al. Fatal systemic disorder caused by biallelic variants in FARSA. Orphanet J Rare Dis. 2022;17:79. doi: 10.1186/s13023-022-02457-9

14. Schuch LA, Forstner M, Rapp CK, Li Y, Smith DEC, Mendes MI, et al. FARS1-related disorders caused by biallelic mutations: look beyond the lungs! Clin Genet. 2021;99(4):552–563. doi: 10.1111/cge.13943

15. Lomuscio S, Cocciadiferro D, Petrizzelli F, Liorni N, Mazza T, Allegorico A et al. Two novel biallelic variants in the FARSA gene: the first Italian case. Genes. 2024;15:412. doi: 10.3390/genes15121573

16. Charbit-Henrion F, Goguyer-Deschaumes R, Borensztajn K, Mirande M, Berthelet J, Rodrigues-Lima F, et al. Systemic inflammatory syndrome in children with FARSA deficiency. Clin Genet. 2022;102(3):211–219. doi: 10.1111/cge.14120