Floyd Type III Tracheal Agenesis with Laryngeal Cleft and Bronchial Segment Absence: A Case Report

Abstract

Introduction: Tracheal agenesis (TA) is a rare, life-threatening congenital anomaly characterized by complete or near-complete absence of the trachea. Floyd Type III, in which both main bronchi arise from the esophagus, represents one of the rarest variants. TA may be associated with other foregut derived malformations such as laryngeal clefts causing aerodigestive tract communication and bronchial hypoplasia or segmental absence, further complicating respiratory function.

Methods: A preterm female neonate with prenatal suspicion of esophageal atresia and cardiac defects underwent postnatal airway assessment via bronchoscopy and CT imaging.

Results: Findings confirmed Floyd Type III TA, an extensive laryngeal cleft, and missing bronchial segments on the left. Complex cardiac anomalies were also present.

Conclusion: This case highlights the importance of early airway imaging and endoscopy in diagnosing major congenital airway malformations and underscores the value of multidisciplinary care in complex neonatal presentations.

Introduction

Tracheal agenesis (TA) is an exceedingly rare congenital anomaly characterized by the complete absence or interruption of the trachea (1). First reported by Payne in 1900, following a failed tracheotomy on a newborn infant, this lethal condition presents a significant challenge to clinicians due to its obscure embryologic origins and high neonatal mortality rates (1). Within the Floyd classification, Type III TA is one of the rarest variants, where both main bronchi arise independently from the esophagus. We present a unique case of postnatally diagnosed Floyd Type III TA in a female neonate, emphasizing the importance of early recognition using modern imaging modalities such as CT with 3D reconstruction and direct endoscopic visualization, which may improve early diagnosis and clinical decision-making in affected infants.

Case Description

A female neonate, born at 35 weeks of gestation via spontaneous vaginal delivery, was admitted immediately for severe respiratory distress. The 32-year-old G4P1 mother had unremarkable prenatal laboratory results. First-trimester ultrasonography demonstrated a viable intrauterine pregnancy. The patient reported minor vaginal spotting, which was managed with progesterone. Continued monitoring at 22 weeks detected cardiac defects and esophageal atresia, prompting referral for specialized care in Pediatric Cardiology, Neonatology, and Pediatric Surgery. By 27 weeks, the fetus exhibited polyhydramnios. Fetal echocardiography confirmed a complex congenital heart defect: double outlet right ventricle (DORV), subaortic ventricular septal defect (VSD), pulmonary atresia, hypoplastic pulmonary arteries, and retrograde flow through a patent ductus arteriosus. Weekly maternal cardiology follow-up was recommended. At 30–31 weeks of gestation, Noninvasive Prenatal Testing (NIPT) was performed, given the mother’s history of recurrent pregnancy losses. This maternal blood test, which screens for common fetal chromosomal abnormalities such as trisomy 21 (Down syndrome), trisomy 18 (Edwards syndrome), and trisomy 13 (Patau syndrome), yielded negative results.

The neonate had APGAR scores of 1 and 4, improving to 9 post-intubation with a size 3.0 uncuffed tube. In the NICU, parameters included blood pressure of 80/50 mmHg, heart rate of 130 bpm, respiratory rate of 50 breaths/min, oxygen saturation of 82% (PSIMV 21/15/12/5), body weight of 2.01 kg, length 44 cm, and head circumference 39 cm. Physical examination revealed frontal bossing and low-set ears; the remainder of the examination was unremarkable.

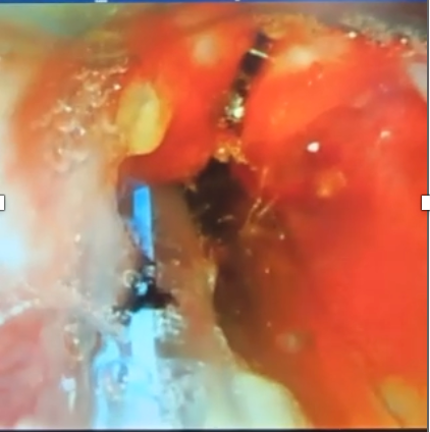

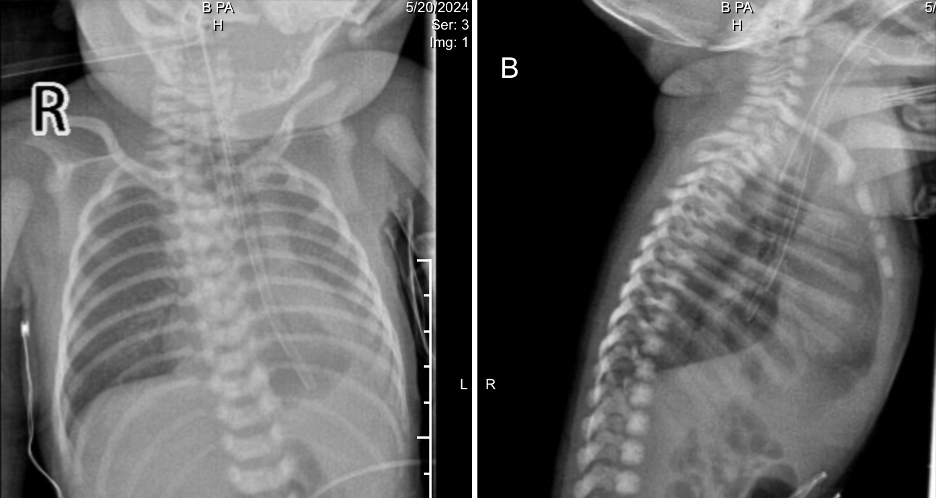

Ventilator air leak prompted re-intubation with a size 3.5 tube. Videolaryngoscopy revealed a slit-like laryngeal deformity (Figure 1.). Bedside echocardiography reaffirmed DORV with pulmonary stenosis. Initial chest radiography (Figure 2.) showed a left lower lobe opacity and a feeding tube in the distal esophagus. The initial impression included neonatal pneumonia with polymalformative features: possible laryngeal cleft, double outlet right ventricle (DORV), esophageal atresia (EA), and tracheoesophageal fistula (TEF). Upon admission, empiric IV antibiotics were started. Referrals to Pediatric Cardiology for evaluation of DORV and to Pediatric Surgery for assessment of suspected EA/TEF were made. A Pediatric Pulmonology consult was eventually obtained for airway assessment due to consideration of laryngotreacheoesophageal cleft.

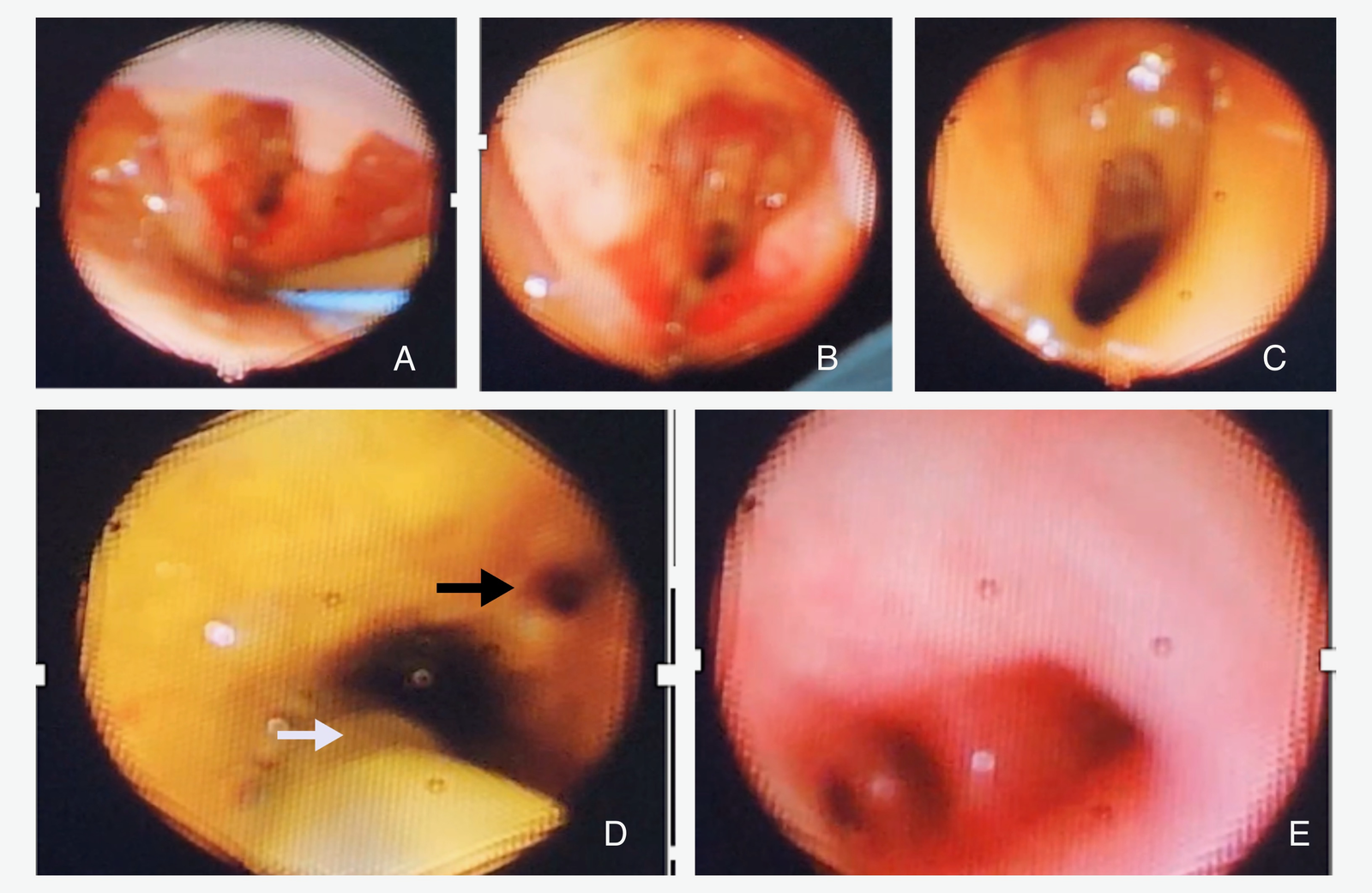

On day three, flexible bronchoscopy was carried out using a 2.8 mm scope, showing extensive upper airway anomalies: inflamed epiglottis, swollen subglottic region, aryepiglottic folds, yellowish secretions likely aspirated gastric fluid, and a long laryngeal cleft extending into the tracheal region (Figure 3. A-C). There were no recognizable tracheal rings. In the supposed location of the left main bronchus, a dilated orifice led to a blind end lined with edematous mucosa. The right main bronchus had a small orifice; the distal bronchial anatomy appeared distorted, but the lobar bronchus of the right lower lobe was identifiable (Figure 3. D-E). The bronchoscopic findings strongly suggested tracheal agenesis with esophageal origins of the bronchial structures.

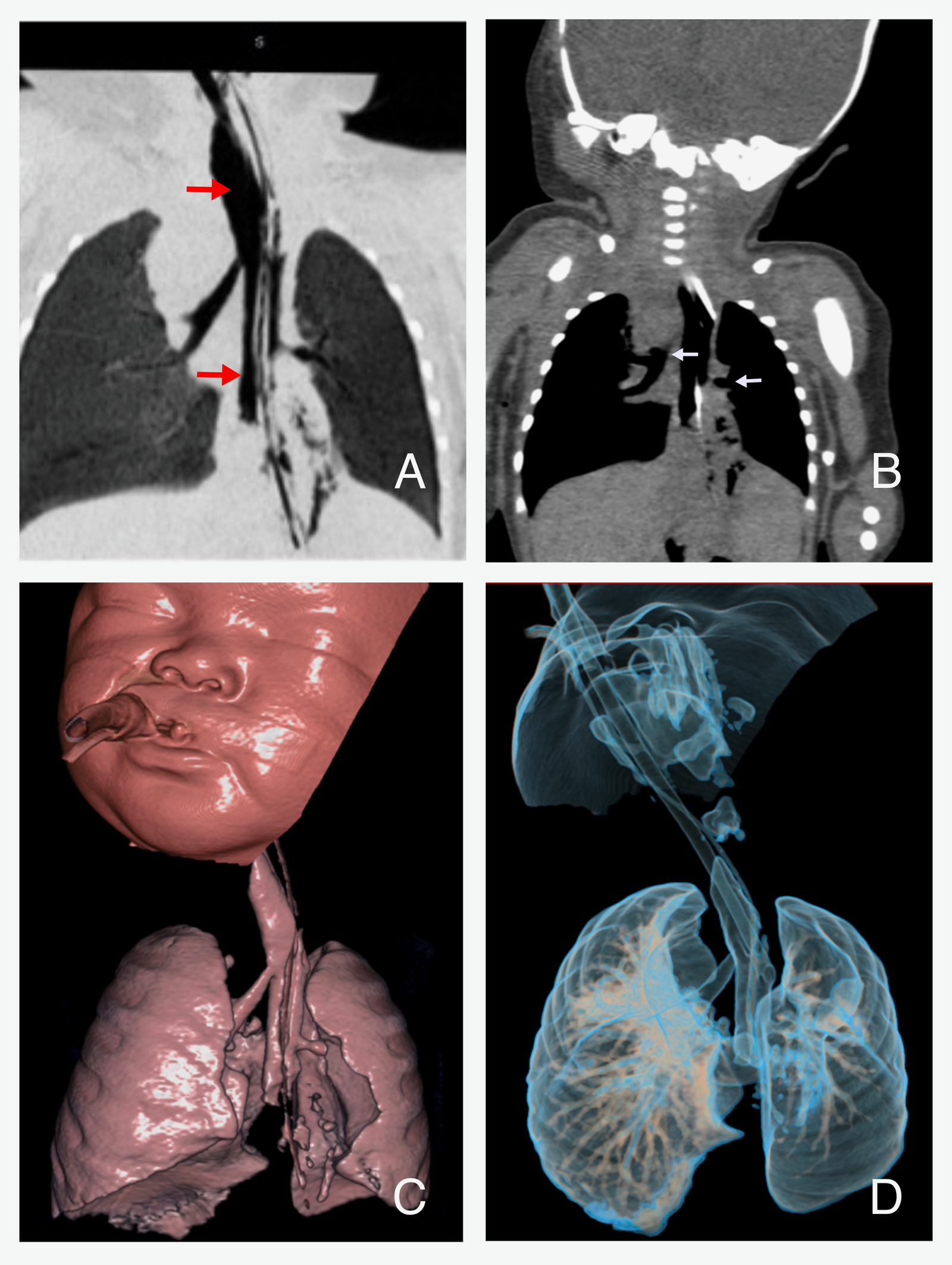

On day four, a plain CT scan of the neck and chest, with 3D airway reconstruction, and abdomen was performed (Figure 4.). It confirmed abnormal airway anatomy consistent with Type III TA: both main bronchi arose from the esophagus, which terminated in a hiatal hernia. The left lung was hypoplastic, likely due to the absence of lower lobar structures, while the right lung appeared normally formed but showed posterior segment consolidation, consistent with aspiration. The liver, spleen, kidneys, urinary bladder and dorsal spine were unremarkable. Genetic consultation was obtained, and chromosomal analysis was performed, which revealed a karyotype of 46, XX in 5 metaphase spread and was negative for trisomy 13, 18, and 21.

Between days five and eight, the patient developed progressive hypoxemia, respiratory deterioration, and signs of nosocomial pneumonia. Despite escalation of ventilatory support and antibiotic therapy, oxygenation remained poor. Surgical intervention was proposed but declined by the parents.

On day nine, the patient presented with severe bradycardia (30 bpm), intractable hypoxemia and oxygen desaturation (60%). After extensive counseling, the family agreed to implement a do-not-resuscitate (DNR) order. The infant died shortly thereafter.

Discussion

TA is a rare anomaly, with prevalence estimated at less than 1:50,000 live births and a slight male predominance (M:F 2:1), although female cases are well documented (2). More than half of the cases occur in preterm infants, and approximately 50% present with polyhydramnios findings that aligned with our patient’s prenatal profile. Additionally, TA may be associated with other congenital airway anomalies, such as laryngeal cleft and bronchial hypoplasia (3). Laryngeal clefts are congenital defects of the posterior laryngotracheal wall, resulting in a persistent communication between the airway and the digestive tract. These clefts may vary in severity depending on how far the cleft extends, from above the vocal cords to involving the cricoid cartilage and extending into the tracheoesophageal region (4). Clinically, they commonly present with choking, aspiration, respiratory distress, or feeding difficulties (5). Bronchial hypoplasia is the underdevelopment of bronchial airways below the level of the main bronchi (or main bronchus), resulting in reduced caliber or absent lobar/sub-lobar segments. Hypoplasia may occur as a primary embryologic error in airway branching, or secondarily due to reduced downstream lung growth often seen in conjunction with tracheal absence or obstruction (6).

Genetically, TA may arise from disrupted foregut patterning during embryogenesis, specifically involving altered expression of dorsal Sox2 and ventral Nkx2-1 homeobox genes (6). Insufficient dorsal-ventral signaling leads to failed partitioning of the trachea from the foregut, resulting in malformation of the airway and potential dorsal misplacement of bronchial buds.

Floyd’s classification distinguishes three types of TA: Type I (proximal tracheal atresia with distal trachea and fistulous connection), Type II (complete tracheal atresia with normal carina), and Type III (main bronchi originating from the esophagus) (7). Type II is the most common (~60%), with Types I and III each comprising ~20%. Our case aligns with Type III, as there was complete tracheal absence and independent esophageal origins of both bronchi, confirmed by both bronchoscopy and CT imaging.

Clinically, TA presents at birth with absent cry (aphonia), severe respiratory distress, cyanosis, and precipitous decline in APGAR scores features prominently seen in our patient (8). Approximately half of affected infants have additional congenital anomalies, often aligned with the VACTERL association, further complicating prognosis and management. In our case, aside from the multiple synchronous airway malformations, DORV, a complex congenital heart disease was also confirmed and significantly affected therapy options and anticipated survival outcomes.

Prenatal diagnosis of TA is challenging, especially when a tracheoesophageal fistula is present (9). Sonographic clues such as absent trachea/tracheal bifurcation, combined with polyhydramnios and non-visualization/absent fetal breathing, may aid early detection. Postnatally, flexible bronchoscopy remains the cornerstone of diagnosis, providing direct visualization of airway architecture and revealing anomalies like absent rings and bronchial origins (10). CT imaging with 3D reconstruction provides corroborative anatomy mapping for surgical planning (11).

No standard surgical treatment exists due to the rarity of TA. Historically, emergent life-sustaining procedures have included esophageal intubation as a temporary airway (12). Definitive surgical strategies typically follow a staged reconstruction plan, starting with proximal esophagostomy, distal esophageal airway creation, and gastrostomy for feeding, followed by reconstructive efforts using grafts such as colon interposition (12). However, long-term outcomes remain bleak and guarded given the complexity and rarity of the condition.

Survival is dismal, with approximately 85% of cases resulting in death within 48 hours (13). While secondary factors such as VACTERL anomalies further worsen prognosis, outcomes in TA with DORV are particularly poor and only a small fraction of live-born infants survive past six months. Our patient’s survival to nine days is notable and highlights the potential role of supportive measures and early diagnostic clarity in extending life, even temporarily.

Conclusion

Tracheal agenesis (TA), particularly Floyd Type III, is a rare and fatal congenital airway malformation that often coexists with other anomalies of foregut origin. In this case, the presence of a long laryngeal cleft and bronchial hypoplasia further complicated the clinical picture and contributed to severe respiratory compromise. Early postnatal diagnosis using flexible bronchoscopy and CT with 3D reconstruction was crucial in identifying the full extent of airway abnormalities and guiding clinical decision-making.

The combination of TA, laryngeal cleft, and complex cardiac anomalies such as double outlet right ventricle significantly limited therapeutic options and survival potential. Despite supportive measures, prognosis remained poor. This case underscores the importance of early airway assessment in neonates with respiratory distress, especially when prenatal findings suggest esophageal or cardiac malformations. Multidisciplinary evaluation plays a pivotal role in achieving timely diagnosis, facilitating informed parental counseling, and guiding management in these exceptionally rare and life-limiting congenital conditions.

Ethical Statement

Approval from the Institutional Review Board (IRB) is not required for single-patient case reports. Upon admission, the patient's parents/legal guardians signed a general informed consent form, which includes permission for the use of anonymized clinical information for educational and scientific purposes, including presentation or publication in scientific forums. All identifying details have been omitted or anonymized to protect the patient's privacy and confidentiality.

Conflict of interest

The authors have no conflict of interest to disclose.

Data availability statement

Data from this case report are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request for educational or research purposes.

Author contributions

Dr. Antero Realista was the principal author and prepared the initial draft of the case report. Drs. Marion Sanchez and Charito Corpuz, who served as part of subspecialty consultants involved in the case, reviewed and provided critical revisions to the manuscript. All authors approved the final version of the report.

Acknowledgements

We gratefully acknowledge the consultants from the Section of Pulmonology at the Philippine Children’s Medical Center for their invaluable guidance and support. We also extend our appreciation to the subspecialty teams involved in the management of this case, including Dr. Lisa Henson (Pediatric Surgery), Dr. Rachelle Niñalga (Pediatric Cardiology), Dr. Monette Faner-Canesco (Clinical and Metabolic Genetics), and Dr. Pamela Lim-Lopez (Pediatric Anesthesiology), for their expertise and collaborative care. Special thanks are extended to our co-fellows in Pediatric Pulmonology and Neonatology for their collaboration and encouragement throughout the course of this case. The principal author also expresses sincere appreciation to all subspecialty physicians whose contributions were instrumental in the management of this complex patient. A heartfelt acknowledgment is given to Dr. Marion Sanchez for her unwavering support and for inspiring the pursuit of this case toward publication. Special thanks are also extended to Drs. Emily Resurreccion, Mary Therese Leopando, and Cesar Ong for their meaningful guidance and lasting inspiration. Most importantly, we give thanks to God for the wisdom, strength, and grace that made this work possible.

References

1. Ergun S, Tewfik T, Daniel S. Tracheal agenesis: a rare but fatal congenital anomaly. McGill J Med. 2011 Jun;13(1):10. doi: 10.26443/mjm.v13i1.241

2. Hirakawa H, Ueno S, Yokoyama S, Soeda J, Tajima T, Mitomi T, Makuuchi H. Tracheal agenesis: a case report. Tokai J Exp Clin Med. 2002 Apr;27(1):1–7.

3. de Groot-van der Mooren MD, Haak MC, Lakeman P, et al. Tracheal agenesis: approach towards this severe diagnosis—case report and review of the literature. Eur J Pediatr. 2012 Mar;171(3):425–431. doi: 10.1007/s00431-011-1563-x

4. Tyler DC, Opitz JM, Reynolds JF. Laryngeal cleft: report of eight patients and a review of the literature. Am J Med Genet. 1985 May;21(1):61–75. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.1320210110

5. De Jong R, Hohman MH, Farahani C. Laryngeal clefts [Internet]. In: StatPearls. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2025 Jan– [updated 2025 Jun 16; cited 2025 Oct 1]. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK616082/

6. Pfeifer M, Rehder H, Gerykova Bujalkova M, Bartsch C, Fritz B, Knopp C, Beckers B, Dohle F, Meyer-Wittkopf M, Axt-Fliedner R, Beribisky AV. Tracheal agenesis versus tracheal atresia: anatomical conditions, pathomechanisms and causes with a possible link to a novel MAPK11 variant in one case. Orphanet J Rare Dis. 2024 Mar 12;19(1):114. doi: 10.1186/s13023-024-03106-z

7. Dijkman K, Andriessen P, Lijnschoten G, Halbertsma F. Failed resuscitation of a newborn due to congenital tracheal agenesis: a case report. Cases J. 2009 Jul;2(1):7212. doi: 10.4076/1757-1626-2-7212

8. Lee S, Jackson J, Lakshminrusimha S, Brown E, Farmer D. Anatomic disorders of the chest and airways. In: Avery’s Diseases of the Newborn. 11th ed. Philadelphia: Elsevier; 2024. p. 626–658.e11. doi: 10.1016/B978-0-323-82823-9.00044-1

9. Rath S, Babarao S. Tracheal agenesis: a lethal malformation. Infant. 2015;11(4):131–132.

10. Abdellah LM, Faseeh NA, Abougabal MS, Farag MM. Retrospective study of congenital airway malformations detected by flexible fiberoptic bronchoscopy in Alexandria University Children’s Hospital. Egypt J Bronchol. 2023 Jul;17(1):31. doi: 10.1186/s43168-023-00208-3

11. Lacalamita MC, Fau S, Bornand A, et al. Tracheal agenesis: optimization of computed tomography diagnosis by airway ventilation. Pediatr Radiol. 2018 Mar;48(3):427–432. doi: 10.1007/s00247-017-4024-5

12. Straughan A. Tracheal agenesis: vertical division of the native esophagus—a novel surgical approach and review of the literature. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol. 2021 Jun;130(6):547–562. doi: 10.1177/0003489420962124

13. Fernández Monteagudo B, Piris Borregas S, Niño Díaz L, Carbayo Jiménez T, Morante Valverde R, Redondo Sedano JV, Moral Pumarega MT. Tracheal agenesis: the importance of teamwork in an uncommon pathology, challenging diagnosis, and high mortality—a case report. Front Pediatr. 2024 Jul;12:1401729. doi: 10.3389/fped.2024.1401729