Medical Thoracoscopy-Guided Talc Pleurodesis in a Pediatric Patient with Malignant Pleural Effusion

Abstract

Background: Pleurodesis is rarely performed in pediatric patients due to limited indications and lack of supporting evidence. However, in cases of malignant pleural effusion, it may serve as a palliative intervention to prevent fluid recurrence.

Methods: We report a 14-year-old male patient with a history of Ewing sarcoma and metastatic pleural disease who was hospitalized for progressive dyspnea. After careful evaluation, a massive right-sided pleural effusion was found as the underlying cause. Palliative treatment was indicated, which was performed in two stages. First, simultaneous pleural fluid drainage with pleural manometry revealed a malignant effusion. The lung elastance of 5.1 cmH2O/L showed possible lung expansion, without trapped lung syndrome. Due to the recurrence of the effusion, the patient underwent medical thoracoscopy and talc pleurodesis.

Results: Under general anesthesia, 1.2 L of fluid was drained via thoracoscopy. Metastatic nodules were visualized on both visceral and parietal pleura. Two grams of sterile talc were insufflated across the pleural surfaces, which resulted in symptomatic improvement.

Conclusion: This case demonstrates the feasibility and technical approach of talc pleurodesis in a pediatric patient. It highlights the utility of thoracoscopic visualization and palliative pleural management in pediatric oncology, as a valuable tool in pediatric interventional pulmonology.

Video

Introduction

Malignant pleural effusion (MPE) is a common complication in adult oncology (1). In adults, pleurodesis with sterile talc is a well-established palliative intervention, providing durable control of recurrent effusions and symptom relief in appropriately selected patients. The technique has been refined over decades and is widely integrated into clinical practice guidelines (2, 3).

In contrast, MPE is exceedingly rare in the pediatric populations, reflecting both the lower incidence of solid tumors and the infrequency of pleural dissemination (3, 4). Consequently, experience with pleurodesis in this age group is limited, and the procedure is rarely reported in the literature (5).

Medical thoracoscopy offers a minimally invasive means of directly visualizing the pleural space, assessing pleural involvement, evacuating fluid, and delivering sclerosing agents under controlled conditions. In adults, this approach allows accurate diagnosis and effective pleurodesis in a single procedure. Its application in pediatrics, however, is uncommon, with most published experience limited to small case series or anecdotal reports (6-8).

Here we present a rare case of medical thoracoscopy-guided talc pleurodesis performed in a 14-year-old patient with metastatic Ewing sarcoma, highlighting both the technical feasibility and palliative benefit of the procedure in an adolescent, while acknowledging the challenges of managing malignant effusion in the setting of progressive pediatric cancer.

Case Description

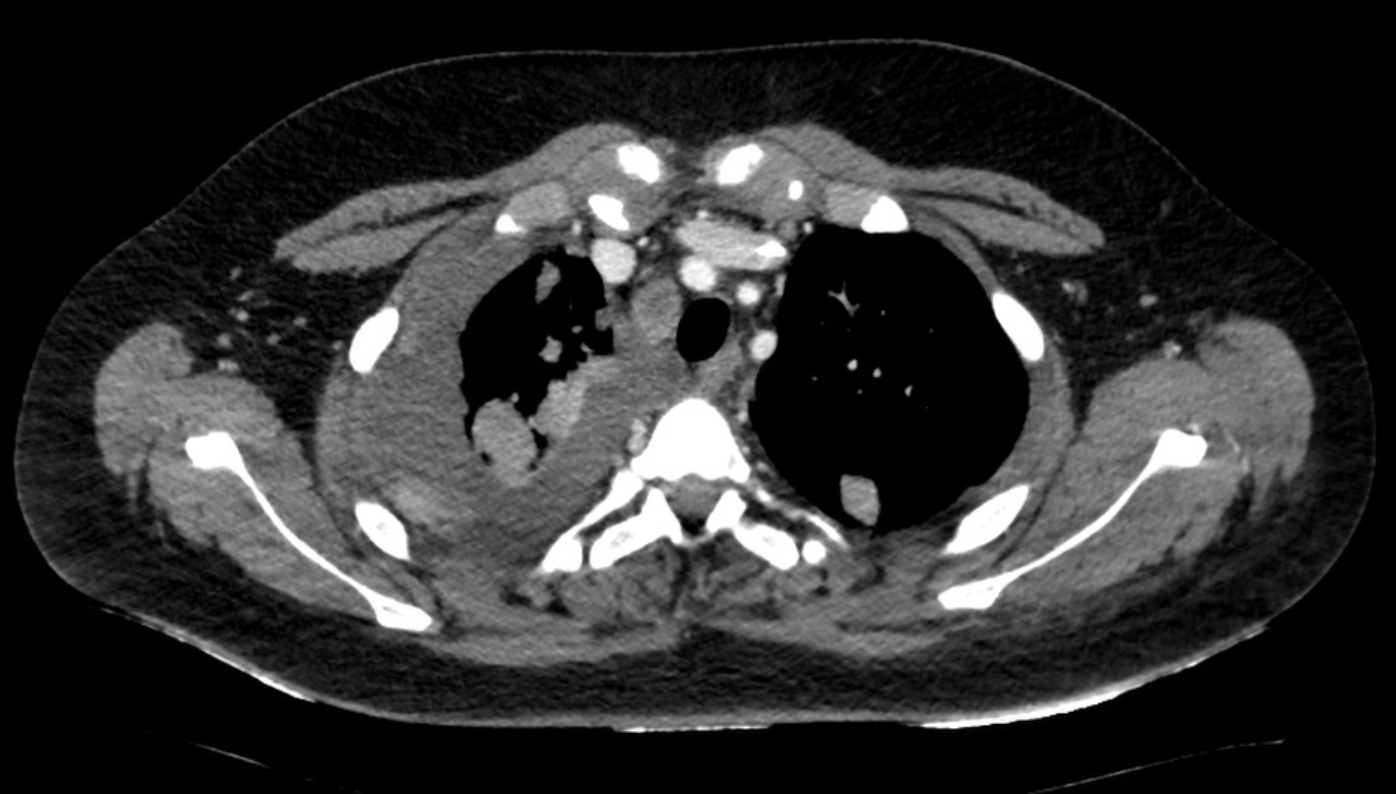

A 14-year-old male with a history of Ewing sarcoma, initially treated with chemotherapy and local control, presented with progressive shortness of breath. Initial lung ultrasound demonstrated a 4.5-cm homogeneous pleural effusion in the right hemithorax, without evidence of loculations. A diagnostic and therapeutic thoracentesis was performed, yielding 500 mL of serosanguinous fluid. Cytology was consistent with malignant effusion. Four days later, repeat ultrasound and chest CT demonstrated recurrence (Figure 1.).

Given the recurrent and symptomatic nature of the effusion, a decision was made to perform medical thoracoscopy and talc pleurodesis under general anesthesia as a palliative treatment.

To evaluate lung expandability and exclude trapped lung physiology, pleural manometry was performed during controlled drainage. The measured lung elastance was 5.1 cmH₂O/L, indicating adequate lung re-expansion potential. A temporary chest drain was inserted for stabilization prior to definitive pleurodesis.

Procedure:

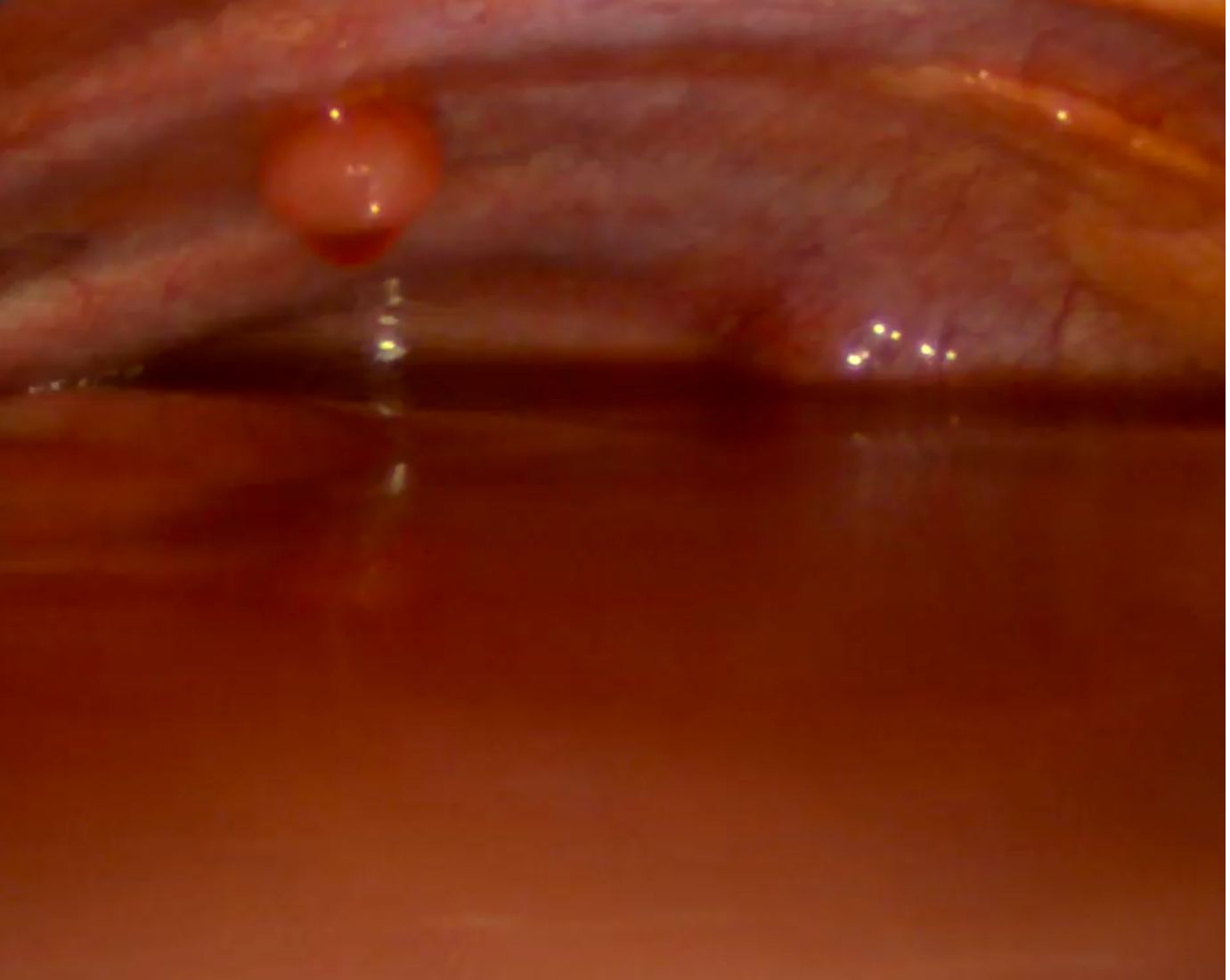

Under general anesthesia with single-lung ventilation, the patient was positioned in the left lateral decubitus position. Following antiseptic preparation and sterile draping, a 1-cm incision was made in the right mid-axillary line. A 5 mm trocar was introduced into the pleural cavity, and a medical thoracoscope was advanced under direct visualization. A large hemorrhagic effusion was encountered (Figure 2.). A secondary incision was created inferiorly for the insertion of a second trocar, which permitted aspiration of the remaining pleural fluid. In total, approximately 1.2 liters were evacuated.

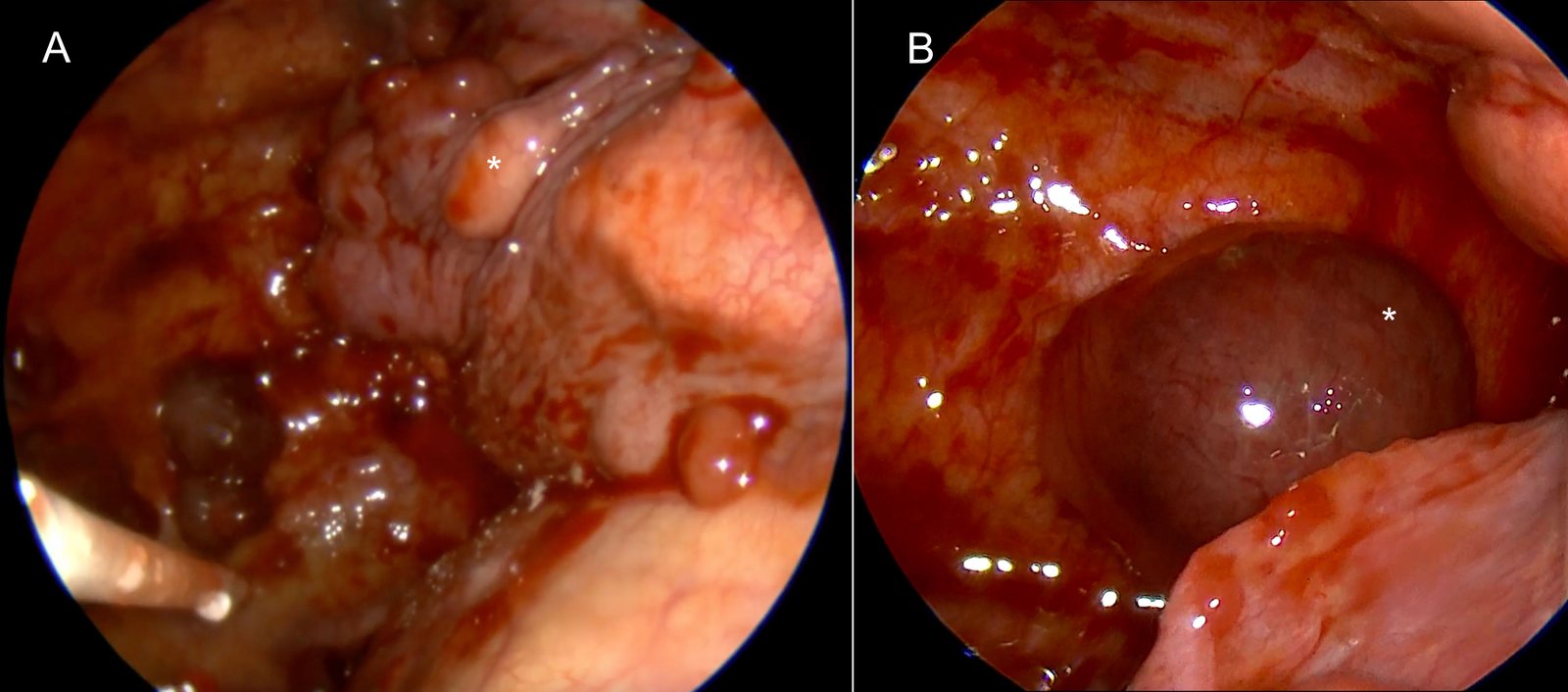

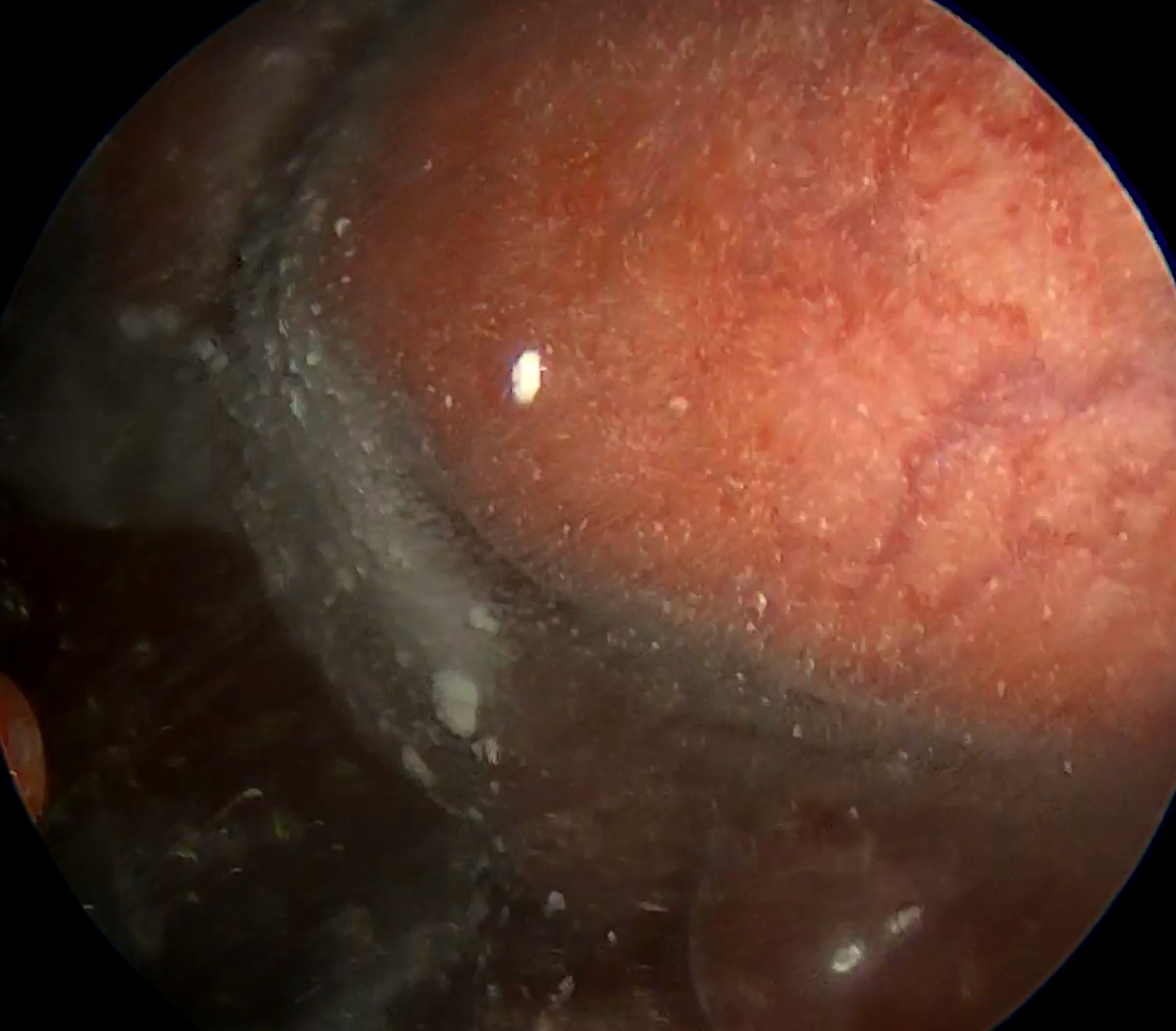

Systematic thoracoscopic inspection revealed multiple metastatic nodules involving both the parietal and visceral pleura (Figure 3A and B). No loculations or fibrin septations were observed. After ensuring complete evacuation of fluid and full lung re-expansion, 2 grams of sterile talc powder were insufflated using a spray device, distributing the agent evenly across the pleural surfaces under direct thoracoscopic guidance (Figure 4.).

At the end of the procedure, a chest tube was placed through the primary port site and connected to negative-pressure drainage. Adequate expansion of the right lung was confirmed thoracoscopically. The patient was transferred to the pediatric intensive care unit for postoperative monitoring.

Outcome:

The patient initially experienced clinical improvement following thoracoscopic talc pleurodesis, with resolution of dyspnea and full re-expansion of the right lung. The chest drain remained in place for three days, at which point it was removed after drainage had stopped. The patient experienced only a transient fever on the first postoperative day. Ten days after the procedure, he again developed progressive shortness of breath. Chest CT demonstrated a new, now, large left-sided pleural effusion and partial loculated fluid collections on the right, in association with progression of previously documented pleural metastases. Given the patient’s rapidly deteriorating clinical condition, we reassessed the therapeutic goals. On the left, a chest drain was inserted, which provided prompt symptomatic relief. On the right, organized blood clot was observed within the pleural space and was left in situ. Given the patient’s progressive clinical decline and the limited expected clinical benefit of performing a repeat talc pleurodesis on the left side compared with drainage alone, we determined that additional pleurodesis would not provide meaningful clinical advantage at that point. Despite further palliative measures, the patient’s disease continued to progress, and he died one month after pleurodesis.

Conclusion

While pleurodesis is well established in adults, its role in children remains poorly defined due to the rarity of malignant effusions in this age group and the lack of prospective data (2, 5)). Our experience demonstrates that the procedure can be safely performed in children, with effective immediate palliation of symptoms and radiographic evidence of lung re-expansion.

Nevertheless, the patient’s subsequent disease progression underscores the limited durability of pleurodesis in the context of rapidly advancing malignancy. This emphasizes the importance of careful patient selection, realistic goal setting, and integration of pleural procedures within a broader palliative care strategy.

Further directions include the need for multicenter registries and prospective studies to characterize outcomes of pleurodesis in pediatric oncology patients. Standardized reporting of technique, agents used, and follow-up data will help establish best practices. In addition, comparative studies between chemical pleurodesis, indwelling pleural catheters, and repeated drainage in children may provide insights into optimizing quality of life while minimizing procedural burden.

This case illustrates the role of medical thoracoscopy-guided pleurodesis as a feasible and effective palliative option in adolescents with malignant effusions. High-quality video documentation of the procedure helps promote awareness of this underutilized approach in pediatric oncology.

Ethical Statement

Ethical approval for this study was obtained from the Ethics Committee of University Hospital Center Osijek.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Data Availability

There are no additional data beyond those included in this report.

Author Contributions

All authors contributed to the study conception and design and were involved in patient management. MS, BO: material preparation, data collection and analysis. MS, PI, HV, TN: writing the first draft of the manuscript and review of literature. BO, TN, TN, HV: review and editing. MS: Supervision. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

References

1. Thomas JM, Musani AI. Malignant pleural effusions: a review. Clin Chest Med. 2013 Sep;34(3):459-71. doi: 10.1016/j.ccm.2013.05.004

2. Antony VB, Loddenkemper R, Astoul P, Boutin C, Goldstraw P, Hott J, Panadero FR, Sahn SA. Management of malignant pleural effusions. Eur Respir J. 2001 Aug;18(2):402-19. doi: 10.1183/09031936.01.00225601

3. Pietsch JB, Whitlock JA, Ford C, Kinney MC. Management of pleural effusions in children with malignant lymphoma. J Pediatr Surg. 1999 Apr;34(4):635-8. doi: 10.1016/S0022-3468(99)90093-3

4. Özge C, Çalikoglu M, Cinel L, Apaydin FD, Özgür ES. Massive Pleural Effusion in an 18-Year-Old Girl with Ewing Sarcoma. Can Respir J. 2004;11(5):363-5. doi: 10.1155/2004/103637

5. Hoffer FA, Hancock ML, Hinds PS, Oigbokie N, Rai SN, Rao B. Pleurodesis for effusions in pediatric oncology patients at end of life. Pediatr Radiol. 2007 Mar;37(3):269-73. doi: 10.1007/s00247-006-0392-y

6. Madhusudan M, Mohite K, Chandra T, Potti P, Jt S. Medical thoracoscopy for tubercular pleural effusion in children. Indian J Pediatr. 2024 Oct;91(10):1088. doi: 10.1007/s12098-024-05158-2

7. Madhusudan M, Potti P, Chandra T, Tukaram SJ. Sago-grain nodules in tubercular pleural effusion. Pediatr Pulmonol. 2024 Dec;59(12):3750-1. doi: 10.1002/ppul.27186

8. Zuccatosta L, Piciucchi S, Martinello S, Sultani F, Oldani S, de Grauw AJ, Maitan S, Corso MR, Poletti V, Ravaglia C. Is there any role for medical thoracoscopy in the treatment of empyema in children? Clin Respir J. 2023 Feb;17(2):105-8. doi: 10.1111/crj.13578