Bronchoscopic Laser Ablation for Subglottic Stenosis

Abstract

Background: Subglottic stenosis (SGS) is a serious condition in children, defined by narrowing of the airway below the vocal cords. Post-intubation injury is the most common acquired cause, particularly in patients with prolonged or traumatic intubation. While open surgical approaches are available, minimally invasive bronchoscopic techniques are increasingly preferred due to reduced morbidity and shorter recovery times.

Methods: We present a one-year-old boy who developed post-intubation SGS after treatment for severe RSV pneumonia. Following discharge, he exhibited persistent stridor and noisy breathing. Flexible bronchoscopy confirmed Cotton-Myer Grade II SGS, prompting consideration of minimally invasive intervention. The patient underwent diode laser ablation delivered through flexible bronchoscopy. This method was selected for its ability to precisely remove fibrotic scar tissue while minimizing damage to the surrounding mucosa and cartilage. The procedure was performed under continuous endoscopic visualization to ensure optimal restoration of airway patency.

Results: The intervention resulted in significant improvement in the airway lumen and reduction in stridor. The child tolerated the procedure without complications. Scheduled follow-up bronchoscopies were planned to monitor for recurrence and to guide further management if necessary.

Conclusion: Flexible bronchoscopy with diode laser therapy is a safe and effective minimally invasive option for treating post-intubation SGS in young children. This technique may help avoid more invasive surgical procedures, including tracheostomy, and plays an important role in multidisciplinary airway management.

Video

Introduction

Subglottic stenosis (SGS) is the most prevalent form of laryngeal stenosis and a significant cause of airway obstruction in the pediatric population. It is broadly categorized as either congenital or acquired, with the latter being the most common, especially in the context of advances in neonatal and pediatric critical care (1).

Post-intubation SGS is a well-recognized complication, particularly in infants and children requiring prolonged mechanical ventilation for conditions such as severe respiratory infections (2, 3). The risk of developing SGS increases with the duration of intubation, presence of a large endotracheal tube, and recurrent intubation attempts, with a reported incidence ranging from 0.9% to 17.4% in some high-risk cohorts (4, 5).

The pathophysiology of post-intubation SGS involves a complex interplay of pressure necrosis, inflammation, and an aberrant wound healing response that leads to the excessive deposition of fibrotic scar tissue just below the vocal cords, the narrowest part of the pediatric airway (6). The clinical presentation of SGS can vary from mild, intermittent stridor to severe respiratory distress depending on the degree of airway narrowing.

Management of SGS is multifaceted and must be tailored to the individual patient based on factors like age, comorbidities, and the severity and location of the stenosis. The goal of treatment is to re-establish an adequate airway lumen. Historically, open reconstructive surgeries, such as laryngotracheal reconstruction, were the standard of care for definitive repair. However, these procedures are invasive and are associated with a long recovery time and potential for complications (7,8).

In recent years, there has been a significant shift towards minimally invasive bronchoscopic techniques, which have become a viable and often preferred alternative for the initial or definitive treatment of less severe stenosis. These techniques include balloon dilation, microdebrider resection, and various forms of laser therapy (9, 10). Advances in pediatric flexible bronchoscopy have expanded its role from a purely diagnostic tool to a powerful interventional modality, allowing for direct visualization and treatment of the airway.

This case report highlights the successful application of bronchoscopic laser treatment via flexible bronchoscopy in a one-year-old boy with post-intubation SGS. This case reinforces the growing body of evidence supporting the use of minimally invasive interventions in the management of pediatric airway pathologies.

Case Description

This is a one-year-old boy with a past medical history of severe Respiratory Syncytial Virus (RSV) pneumonia requiring intubation and mechanical ventilation one month prior. Post-discharge, parents observed persistent noisy breathing, which progressively worsened thus seeking medical attention. Physical examination upon admission revealed a mildly respiratory distress child with biphasic stridor. Given the history of intubation and stridor, a diagnosis of acquired post-intubation subglottic stenosis (SGS) was highly suspected.

To confirm the diagnosis and to assess the severity of the stenosis, a flexible bronchoscopy was performed under sedation. The patient was sedated with a combination of intravenous midazolam (0.1 mg/kg) for anxiolysis and amnesia, and intravenous ketamine (1-2 mg/kg) for its potent dissociative and analgesic properties, which allowed for a stable airway and spontaneous respiration throughout the procedure. The child was maintained on spontaneous ventilation using the Soong ventilation (11) method with high flow nasal cannula 5L of flow rate with initial FiO2 100%. A novel non-invasive ventilation technique that involves a pharyngeal oxygen catheter and intermittent nose closure with abdominal compressions. This approach provided adequate oxygenation and positive pressure ventilation without the need for an endotracheal tube or laryngeal mask airway, which would have obscured the stenotic site.

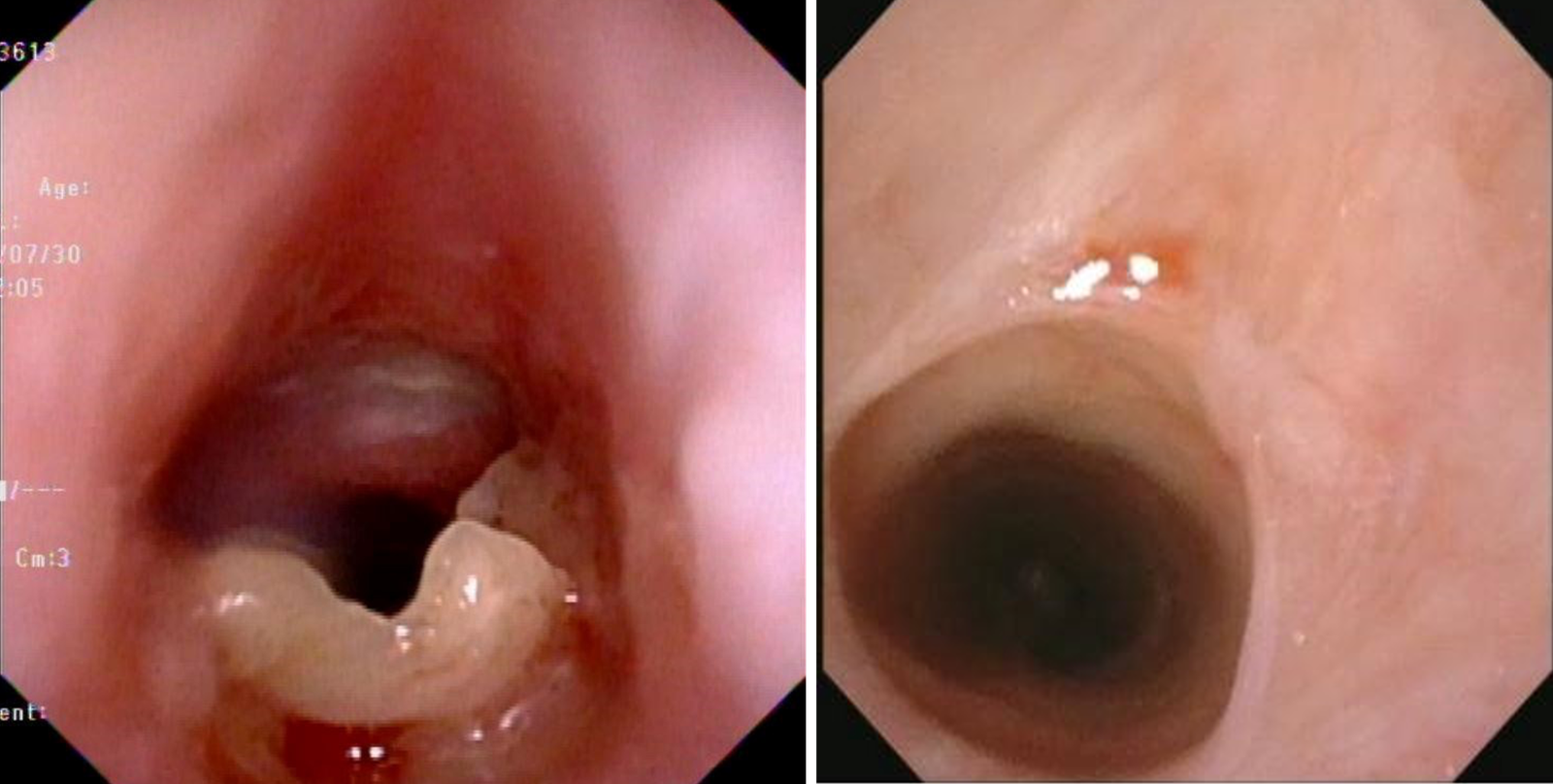

During the procedure, a significant narrowing of the subglottic airway was visualized, approximately 2 mm below the vocal cords. The stenotic lesion was noted to be fibrotic, with an estimated Grade II stenosis based on the Cotton-Myer grading system (Figure 1), obstructing approximately 70% of the airway lumen. The vocal cords had normal mobility and appearance.

Based on the bronchoscopic findings and the patient's clinical symptoms, it was decided to proceed with an immediate therapeutic intervention during the same session. Utilizing the flexible bronchoscope, a Diode laser was advanced through the working channel with the bronchoscope. During laser ablation, the high flow nasal cannula settings, especially FiO2 was reduced to 30% to minimize the risk of airway fire. The contact Diode laser with power of 5w in continuous mode was used to precisely ablate the fibrotic scar tissue, systematically vaporizing the stenotic ring. Care was taken to avoid a full-thickness ablation and to protect the cricoid cartilage. Following the laser ablation, the airway was re-examined, revealing a significant improvement in the airway patency. The patient tolerated the procedure well with no complications.

Conclusion

The successful outcome in this case aligns with recent literature demonstrating the efficacy of bronchoscopic interventions for acquired pediatric SGS(3). The use of diode lasers in pediatric airway surgery has emerged as a significant advancement, offering a precise, effective, and often safer alternative to traditional surgical methods and other laser technologies. With a growing body of evidence supporting its application for a variety of conditions, the diode laser is proving to be a valuable instrument, demonstrating notable success in treating complex airway pathologies in children (12).

The management of pediatric SGS requires a comprehensive and individualized approach. The ability to perform both diagnostic and therapeutic procedures in a single setting, as demonstrated in this case, enhances procedural efficiency and reduces the need for multiple anesthetic exposures for the patient. This case report reinforces the critical role of interventional pulmonology to optimize outcomes for young patients with complex airway pathologies.

Ethical Statement

This case report was conducted in accordance with institutional guidelines and does not require ethics committee approval. Patient consent was not required as all identifying information had been anonymized.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Data Availability

There are no additional data beyond those included in this report.

Author Contributions

S. H. Tan – Original draft and literature review. W. J. Soong – Literature review and manuscript supervision.

References

1. Marston AP, White DR. Subglottic stenosis. Clin Perinatol. 2018 Dec;45(4):787–804. doi: 10.1016/j.clp.2018.07.013

2. Ravikumar N, Ho E, Wagh A, Murgu S. The role of bronchoscopy in the multidisciplinary approach to benign tracheal stenosis. J Thorac Dis. 2023 Jul;15(7):3998–4015. doi: 10.21037/jtd-22-1734

3. Lin CH, Chen CH, Soong WJ, Yong SB. Postintubation tracheal stenosis in children: a review focused on bronchoscopic treatment. Tungs’ Med J. 2025 Jan–Jun;19(1):12–18. doi: 10.4103/ETMJ.ETMJ-D-24-00026

4. Schweiger C, Marostica PJ, Smith MM, Manica D, Carvalho PR, Kuhl G. Incidence of post-intubation subglottic stenosis in children: a prospective study. J Laryngol Otol. 2013 May;127(4):399–403. doi:10.1017/S002221511300025X

5. Monnier P. Acquired post-intubation and tracheostomy-related stenoses. InPediatric Airway Surgery: Management of Laryngotracheal Stenosis in Infants and Children 2010 Sep 30 (pp. 183-198). Berlin, Heidelberg: Springer Berlin Heidelberg.

6. Dorris ER, Russell J, Murphy M. Post-intubation subglottic stenosis: aetiology at the cellular and molecular level. Eur Respir Rev. 2021 Jan;30(159):200218. doi: 10.1183/16000617.0218-2020

7. Maldonado F, Loiselle A, Depew ZS, Edell ES, Ekbom DC, Malinchoc M, Hagen CE, Alon E, Kasperbauer JL. Idiopathic subglottic stenosis: an evolving therapeutic algorithm. Laryngoscope. 2014 Feb;124(2):498–503. doi: 10.1002/lary.24287

8. Feinstein AJ, Goel A, Raghavan G, Long J, Chhetri DK, Berke GS, Mendelsohn AH. Endoscopic management of subglottic stenosis. JAMA Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2017 May;143(5):500–505. doi: 10.1001/jamaoto.2016.4131

9. Zhang GL, Wang CJ, Peng S, Gu RX, Xie XH, Luo J, Luo ZX. The effect of interventional treatment with bronchoscopy in 10 children with acquired subglottic stenosis. Sichuan Da Xue Xue Bao Yi Xue Ban. 2022 Jan;53(1):166–170. doi: 10.12182/20220160109

10. Jiao A, Liu F, Lerner AD, Rao X, Guo Y, Meng C, Pan Y, Li G, Li Z, Wang F, Zhao J, Ma Y, Liu X, Ni X, Shen K. Effective treatment of post-intubation subglottic stenosis in children with holmium laser therapy and cryotherapy via flexible bronchoscopy. Pediatr Investig. 2019 Mar;3(1):9–16. doi: 10.1002/ped4.12113

11. Soong WJ, Jeng MJ, Lee YS, Tsao PC, Harloff M, Soong YH. A novel technique of non-invasive ventilation: pharyngeal oxygen with nose-closure and abdominal-compression – aid for pediatric flexible bronchoscopy. Pediatr Pulmonol. 2015 Jun;50(6):568–575. doi: 10.1002/ppul.23028

12. Bajaj Y, Pegg D, Gunasekaran S, Knight LC. Diode laser for paediatric airway procedures: a useful tool. Int J Clin Pract. 2010 Jan;64(1):51–54. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-1241.2008.01734.x